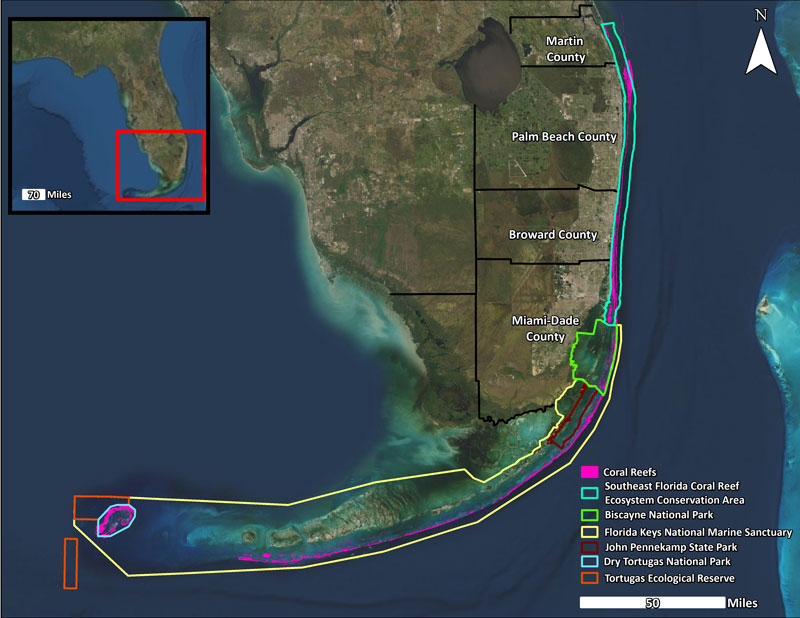

Right off the shores of Florida’s East Coast is the only coral reef system in the continental United States of America. Stretching almost 350 miles, the Florida Coral Reef reaches as far north as the St. Lucie inlet down to the Dry Tortugas, past the Florida Keys. This reef tract emerged over 10,000 years ago following the last Ice Age and is made up of over 45 known species of stony corals, 35 species of octocorals, and over 70 species of sponges. Not only does this reef bring amazing colors and patterns to our underwater landscape, but coral reefs support the biodiversity of our ocean by providing shelter, food, and breeding grounds to species big and small.

Caption: Florida’s Coral Reef Map with Management Boxes (Image Source: FDEP)

Why is Florida’s Coral Reef Important?

Coral reefs are extremely biodiverse, with the unique shapes and structures of different coral and sponge species providing many benefits to marine organisms. While only occupying 1% of our ocean floor, coral reefs are home to more than 25% of marine organisms that depend on them for food and shelter. Some marine life, like parrotfish, eat the corals, scraping off their symbiotic algae called zooxanthellae, and excreting the coral skeleton as sand. Many species of shrimp, worms, snails, and crabs call these reefs home, feeding on parasites, algae, and plankton. In turn, these organisms keep the reef healthy by filtering the water and removing detritus, overgrowing algae, and harmful parasites. A healthy reef attracts many species of fish that hunt on the reef and make use of its nooks and crannies to hide from predators, especially juveniles.

Not only do coral reef ecosystems provide crucial habitats for all types of marine organisms, but they protect us as well. Coral reefs are our coastlines’ first line of defense against storms and hurricanes that can cause a storm surge that erodes our shorelines. The structure of coral reefs on the seafloor obstructs waves, dissipating their energy and effectively reducing their speed and strength once they reach our shores. This shoreline protection is extremely valuable to the economies of coastal cities, with the Coastal Protection Value (CPV) estimated to be about 9 billion USD annually, reducing the need to spend on flood protection and restoring eroded coastlines.

Fighting Climate Change and Anthropogenic Threats

Despite their invaluable positive impact on coastal economies through shoreline protection and tourism, coral reefs are facing global decline. Sea level temperature increases due to global warming are perhaps the most significant threat to corals, which are extremely sensitive to heat stress. When sea temperatures are above the threshold that corals can tolerate for extended amounts of time, corals bleach and may die. Coral bleaching occurs when heat stress causes them to expel their zooxanthellae, the photosynthetic algae living within their tissue, causing them to lose their color and appear white. The Florida Reef Tract experienced the worst coral bleaching event recorded in July 2023 when water temperatures rose to over 101 degrees Fahrenheit in Manatee Bay, Florida.

In recent years, coral reefs in the Caribbean have been decimated by a new threat: Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease (SCTLD). SCTLD emerged in the Florida Reef Tract in 2014 following a bleaching event and has since spread to other regions of the Caribbean. The exact cause is unknown, but scientists believe it is spread through a bacterial pathogen in the water, causing lesions on the surface of stony corals. Unfortunately for these extremely sensitive animals, SCTLD spreads rapidly, and coral typically dies within weeks or months of infection. Fortunately, there is hope for our reefs, as scientists have developed an amoxicillin antibiotic that has been proven to stop the progression of SCTLD when applied topically to infected coral. SeaKeepers is proud to have collaborated with the Perry Institute of Marine Science (PIMS) this year to assist in their research and monitor the progression of SCTLD in the Bahamas, treating over 400 infected corals with antibiotics to stop the spread of the disease.

Caption: SCTLD Assessments and Treatment with the Perry Institute of Marine Science, June 2024(Photographer: Katie Sheahan)

What can you do to save our reefs?

You don’t have to be a scientist to play a role in reef conservation! Being a responsible snorkeler and boater when near coral reefs plays a crucial role in keeping reefs healthy. Boaters should be sure to never drop their anchor onto a reef, the force of which could scar and break many corals. When entering the ocean, swimmers should opt for reef-safe sunscreens that do not include the typical chemicals that are toxic to corals (see our blog post on reef-safe sunscreen for more information). Divers and snorkelers committed to conservation can act as citizen scientists through the Southeast Florida Action Network (SEAFAN) BleachWatch training, which creates an observer network to report early warnings of coral bleaching and disease to the FDEP.

Snorkeling or diving over a coral reef is a life-changing experience for many. From the vibrant colors to the incredible array of species of marine life, it is an insight into the delicate yet complex balance of marine ecosystems. As climate change surges on, we must act now to preserve what life is left on reefs around the world.

References:

Biodiversity. Coral Reef Alliance. (2021, September 1).

BleachWatch: An Early Warning Network for Coral Bleaching and Disease. Friends of Our Florida Reefs. (n.d.).

Boris T. van Zanten, Pieter J.H. van Beukering, Alfred J. Wagtendonk. Coastal protection by coral reefs: A framework for spatial assessment and economic valuation, Ocean & Coastal Management, Volume 96, 2014, Pages 94-103, ISSN 0964-5691

Carla I. Elliff, Iracema R. Silva. Coral reefs as the first line of defense: Shoreline protection in face of climate change, Marine Environmental Research, Volume 127, 2017, Pages 148-154, ISSN 0141-1136

Coral Bleaching. Florida Fish And Wildlife Conservation Commission. (n.d.).

Estrada-Saldívar, N., Molina-Hernández, A., Pérez-Cervantes, E. et al Reef-scale impacts of the stony coral tissue loss disease outbreak. Coral Reefs 39, 861–866 (2020).

Florida’s Coral Reef. Florida Department of Environmental Protection. (2024, May 22).

Florida Department of Environmental Protection. (2022, May 12). Florida’s Coral Reef.

Photo references:

Florida’s Coral Reef Map with Management Boxes. Florida Department of Environmental Protection. (n.d.).